Stress Hormones and Preference for Palatable Foods

Evidence-based exploration of stress-induced changes in food preference

Overview

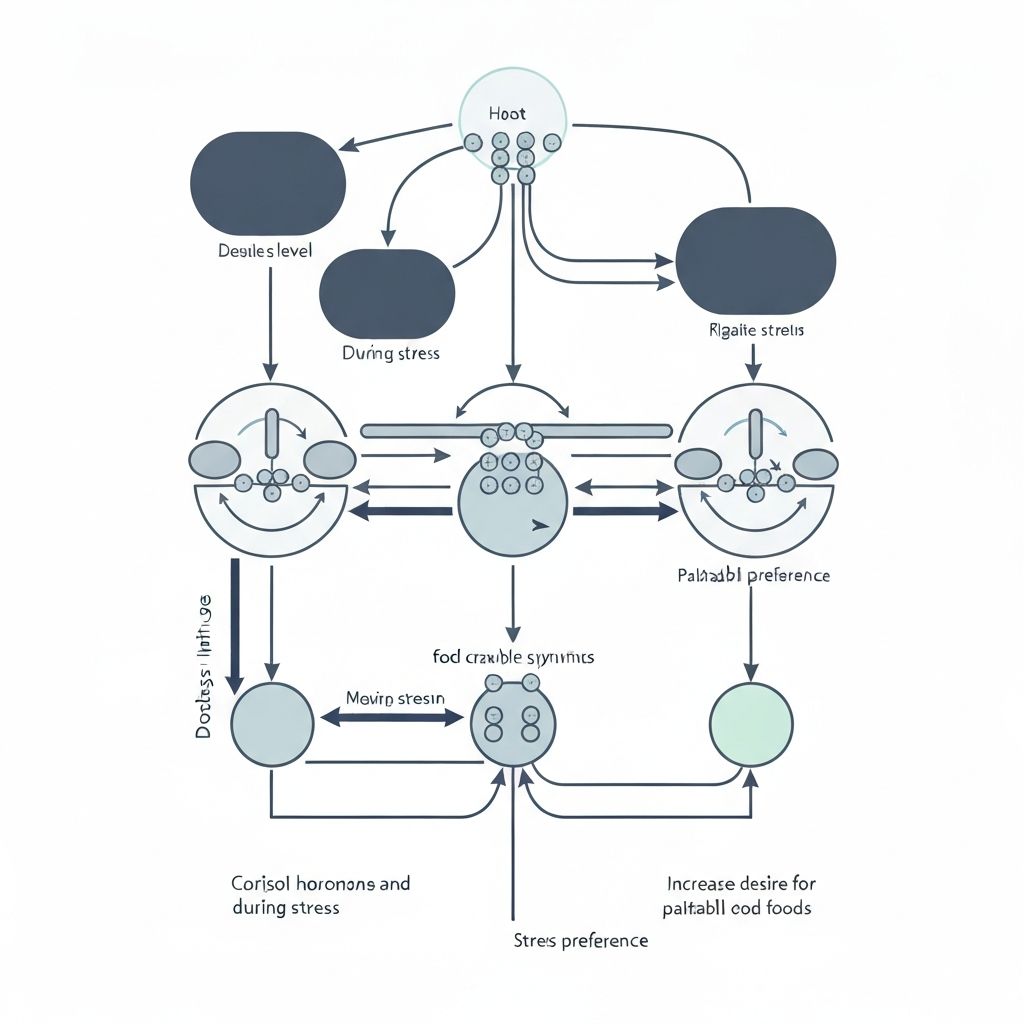

Acute and chronic stress trigger neurobiological changes that shift food preferences toward palatable, high-calorie foods—particularly those high in sugar and fat. This phenomenon reflects the action of stress hormones on appetite-regulating brain regions and represents an example of how psychological and environmental stressors can influence eating behaviour through physiological pathways.

Cortisol and the Stress Response

Cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid stress hormone, is secreted by the adrenal glands in response to both acute and chronic stressors. During stress, cortisol levels rise, triggering a cascade of metabolic and behavioural changes designed to prepare the body for action.

Key effects of elevated cortisol include:

- Increased glucose production and blood glucose elevation

- Immune system modulation

- Altered appetite signalling

- Enhanced attention to threat-related stimuli

- Changes in food preference patterns

Stress-Induced Shift Toward Palatable Foods

Research consistently demonstrates that stress increases preference for palatable foods—foods high in sugar, fat, or both. This shift occurs through multiple mechanisms:

1. Hedonic hunger activation: Stress enhances hedonic hunger (eating for pleasure) relative to homeostatic hunger (eating for metabolic need). This is mediated by cortisol effects on the reward system, making palatable foods more appealing.

2. Dampening of satiety signals: Chronic stress may reduce leptin sensitivity, making individuals less responsive to satiety signals and more prone to overeating palatable foods.

3. Increased reward sensitivity: Stress can enhance dopamine responses to food rewards, making palatable foods more reinforcing and intensifying cravings.

Brain Regions Involved in Stress-Induced Eating

Multiple brain regions mediate the relationship between stress hormones and food preference:

- Amygdala: Processes emotional aspects of stress and interacts with reward systems to increase preference for comfort foods

- Hypothalamus: Contains appetite-regulating centers sensitive to both stress signals and metabolic state

- Prefrontal Cortex: Involved in inhibitory control and decision-making; stress can reduce its function, weakening restraint over food intake

- Nucleus Accumbens: Reward-processing region showing enhanced responsiveness to food cues during stress

Cortisol's Metabolic Effects

Beyond neurobiological effects, cortisol directly influences metabolism in ways that can intensify craving:

- Increased blood glucose: Cortisol promotes glucose production, which can trigger hunger and craving signals despite adequate energy availability

- Altered adipose tissue deposition: Chronic stress and elevated cortisol are associated with preferential deposition of fat in visceral regions

- Insulin sensitivity changes: Chronic stress may reduce insulin sensitivity, affecting glucose regulation and hunger signals

Other Stress Hormones

Beyond cortisol, other hormones released during stress contribute to altered food preferences:

- Adrenaline (Epinephrine): Released during acute stress, promoting energy mobilization and affecting appetite

- CRH (Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone): Initiates the stress response cascade and can directly influence appetite regulation

- NPY (Neuropeptide Y): Increases during stress and directly promotes appetite, particularly for high-fat and high-sugar foods

Individual Differences in Stress-Induced Eating

Important to note: not all individuals show increased food intake or cravings during stress. Individual differences include:

- Genetic factors affecting stress hormone sensitivity

- Personality traits and coping strategies

- Prior food experiences and conditioned associations

- Current metabolic state and hunger levels

- Type and duration of stressor

Some individuals respond to stress with increased appetite and food intake, while others experience appetite suppression. These individual variations reflect differences in stress physiology and psychological processing.

Evidence from Research

Research findings demonstrate:

- Acute stress increases preference for high-calorie foods in laboratory settings

- Chronic stress exposure is associated with sustained increases in snacking and consumption of palatable foods

- Elevated cortisol correlates with increased intake of sweet and fatty foods

- Stress-reduced individuals show reduced preference for palatable foods compared to stressed individuals

Implications for Understanding Craving

The stress-craving connection illustrates how emotional and environmental stressors translate into biological signals that influence food preferences and craving intensity. During periods of stress, the brain prioritizes reward-seeking behaviour, making palatable foods more appealing and intensifying craving responses.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes. This material describes observed patterns in stress physiology and does not constitute medical or personal advice. Individual responses to stress and food vary substantially. Consult qualified healthcare providers regarding stress-related eating concerns.

Return to research articles:

← Back to Research Articles